The atom model with the electrons going around the nucleus, is inspired by the solar system. The better model doesn’t look anything alike. This is a naturalistic circular fallacy

If atoms were like the solar system, all of the electron orbits would lose energy and decay by emitting electromagnetic radiation.

The same type of decay does occur in the solar system as the planets emit gravitational radiation, but the decay rate is so miniscule we can’t really detect it.

Could you explain what you mean by “emitting gravitational radiation”? Gravity is how we perceive distortions in spacetime, the strength of which being determined by the mass of the objects. I understand that orbits can “decay”, but that is not the same as radioactive decay.

General relativity is famously difficult to understand, and I don’t claim to fully understand it, so I’m going to fall back to the famous rubber sheet model.

Imagine the Earth in empty space. The mass of the Earth causes spacetime curvature that extends outward away from the Earth. However, if you look a single little patch of spacetime at some distance, say, 1000 km away, that little patch doesn’t know that it has to be curved because the Earth is 1000 km away. It doesn’t know where the Earth is. It just knows that its neighboring patch is a little bit more curved in the direction that leads to Earth, and its other neighbor is a little bit less curved going away from Earth. This essentially restates the principle of locality: all physics is local physics, and there is no spooky action at a distance.

Now imagine that the Earth moves by some small distance dx in a small time dt. Going back to our little patch of spacetime, it doesn’t know that the Earth moved. So how does it change its curvature to match the new position of the Earth? It changes when its neighbors change. When the Earth moves, the spacetime immediately near the Earth stretches and bends first, then spacetime a little further away, and so on and so on. This process doesn’t happen instantaneously; it takes time for changes to propagate to longer distances. The theory predicts that disturbances and ripples will propagate via waves, called gravitational waves, and that these waves travel at the same speed of light as electromagnetic waves.

Notice I called these spacetime waves “gravitational waves.” It is common to use the term “gravity waves” for typical water waves, of the kind you might see at the beach. Those are not the same type of wave.

Now let’s talk about energy. The Earth in the solar system has some energy, including translational and rotational kinetic energy, gravitational potential energy as it sits in the Sun’s gravity well, and of course its own thermal energy and rest mass. Waves have the ability to transport energy from one location to another without transporting matter, mass, or electric charge. Spacetime waves are not any different. Because the Earth is moving in a periodic motion, it produces a periodic spacetime wave that propagates outward away from the solar system, and that spacetime wave carries some amount of energy away from the solar system. Where does that energy come from? It comes from the Earth, mainly from the Earth’s kinetic energy.

So the story is that the gravitational waves are very, very, very slightly causing the Earth to slow down in its orbit. And following the laws of orbital mechanics, this causes the Earth to fall closer to the Sun. The result is that over the long term, the radius of the Earth’s orbit gets smaller. Alternatively, the Earth’s circular orbit is an illusion, and it’s actually spiraling inward on a very, very, tightly packed spiral. That’s what I meant by “orbital decay.”

I find it hard to overstate just how small this gravitational radiation effect is for a typical solar system situation. We have an observatory called LIGO that can detect gravitational waves. It can measure a variation in distance of a tunnel of several kilometers down to well less than a single proton diameter. (Remember, this is trying to detect disturbances in space and time itself). Even still, it is only able to detect gravitational waves from the most powerful kinds of gravitational events–mergers of black holes and the like.

Essentially: Spacetime is very “stiff” and gravity is very weak.

That was a great read, thank you

Thank you very much for the thought out explanation, i think im beginning to grasp the concept. To summarize to make sure:

- accelerating mass causes gravitational waves

- two bodies orbiting eachother are also accelerating towards eachother by virtue of centripetal force.

- the energy to generate this wave is stripped directly from the kinetic energy of the system, causing the orbit to decay.

So the comparison to atoms releasing EM energy is a bit more apt then I initially thought. Thanks again!

They weren’t talking about radioactive decay, electrons are stable. They were talking about electrically charged particles emitting electromagnetic radiation when accelerated. (Circular movement is accelerated, see centripetal force) Since they use energy for this, they would very quickly fall into the nucleus (if I remember correctly, in around 10^-14 s).

Bodies with mass also emit gravitational waves when accelerated, but much less.

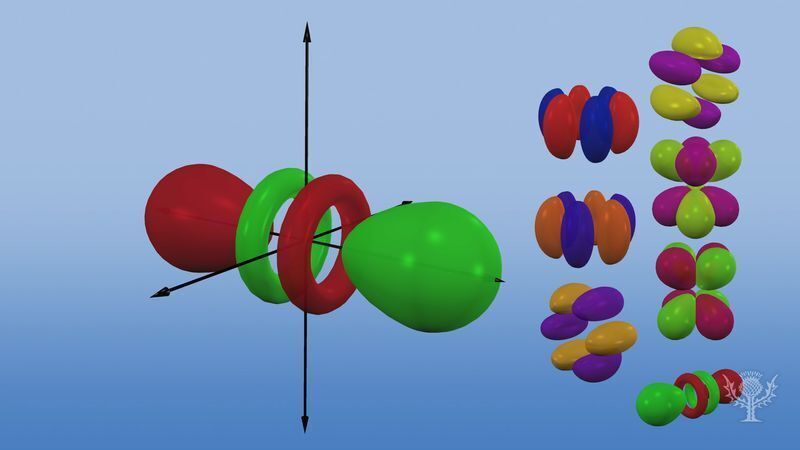

Electrons do orbit like planets in the solar system however they’re also waves. Which is what gives the set radii they can orbit at and keeps it all stable. The orbits can and do change due to the emission or absorption of certain quanta of radiation.

So saying like is fine. It’s not an exact description but more of a simile to help understanding. They do orbit like a solar system. Saying electrons orbit the same as a solar system would be incorrect. That’s when the maths doesn’t work and the electrons orbit would decay.

that is not what i’ve learned, afaik electrons do not orbit with any sort of movement, and in fact talking about positions and movements at all on such a small scale is misleading.

What i’ve learned is that electrons exist as a probability cloud, with a certain chance to observe them in any given position around the atom depending on the orbital and the amount of other electrons.

Comparing it to gravitational orbits is just basically entirely incorrect, and certainly isn’t going to help someone pass advanced physics classes.

If they don’t orbit with any kind of movement then what does that say about Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle?

We know their mass. So once observed we would know everything about them.

Unless your saying they just some how jump from one random point in that probability cloud to another?

i’m not sure why you think the uncertainty principle is a “gotcha”, it specifically states that you can’t know both the position and momentum of a particle and thus explicitly contradicts your claim that we’d know everything about them because we know their mass.

I can’t be arsed to write out a whole scientific paper here so i’ll just link to the probability cloud model of orbitals and hope you can make sense of that.

You specifically said “electrons do not orbit with any kind of movement”

So by your own argument they’re not moving. We know the mass. So if we find one by your logic we know everything about it.

Yes that is the probability cloud model well done.

However my point again. You seem to think saying this renders the simile of planetary orbit obsolete. It doesn’t it’s a simile. It’s a way of explaining something that doesn’t have to exactly explain it.

If someone said “that fell on my head like a ton of bricks” would you go and examine the object and check it was exactly a ton of bricks or that it exactly exhibited the properties of a ton of bricks?

Or perhaps would you understand something from that about what had happened to them.

You may find this useful. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simile

Ok, hear me out for curiosity sake. What happens if you slow down time to magnitudes less then you can observe?

The passage of time is always consistent for the observer, in that a clock next to them will always tick at the same interval. The tidal wave planet from Interstellar is a good example of this, in that only a short time had elapsed for the people on the surface, but back home on earth over 20 years went by. -Edited, didnt explain correcty the first time

Yes, because everybody knows the earth is in the sun’s p orbital

What if our solar system is just another balloon animal???

More believable than the meme.

Nono, these are d orbitals. Although p orbitals are equally silly.

I stand corrected. I should have checked; I mean, I’m not a quantum astrophysicist.

I just woke up and read that as “quantum aristocrat”.

Lol. For all I know I could be a quantum aristocrat, but whenever I open my bank account its wave function collapses to about $300

these are f orbitals, there is 5 of d orbitals

Just testing how deep Cunninghams law will go haha

that only works outside of dead internet

There was a guy on the net years ago who claimed that the entire universe is an electron on a plutonium atom. He made a religion out of it, wrote hymns to the atom (or, more precisely, changed the words of Christian hymns, clumsily fitting in references to plutonium atoms) and even legally changed his name to Archimedes Plutonium.

That sounds like something out of a fallout fanfiction

With a name like that I imagine his cause of death might be in the radioactive “bathtub” of a nuclear rod cooling pool

I always find it fascinating how specific those theories become. Want to believe that our universe is just some sort of quark in a bigger universe we can’t know anything about? Fine. Doesn’t make terribly much sense, but what does at that scale anyway? But then going on and being sure that that bigger thing must be Plutonium? Why? How?

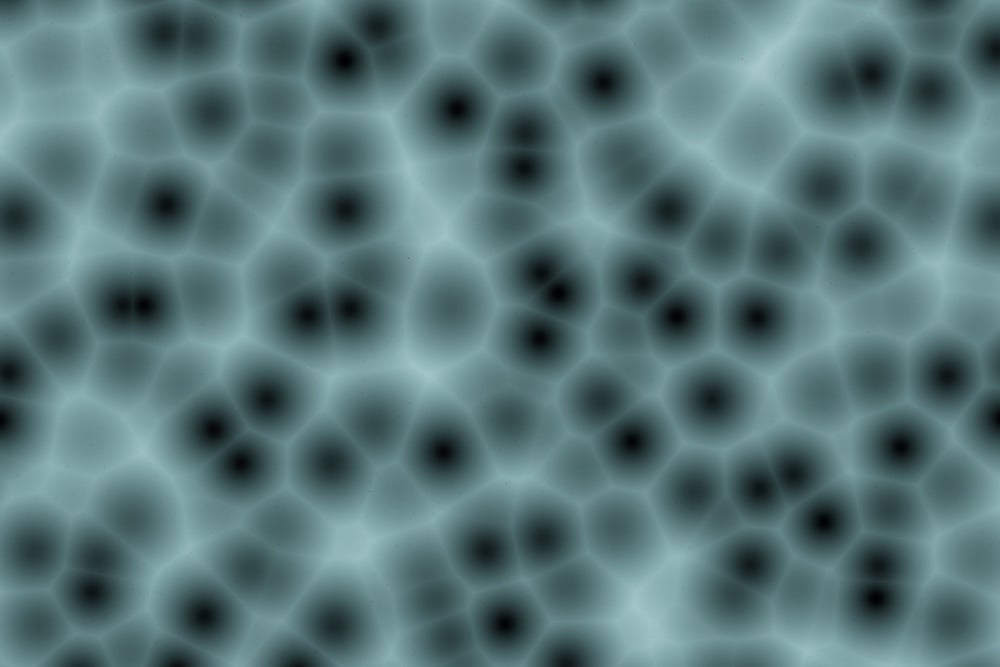

Look, I’m not saying our universe exists as a node in an infinite fractal of repeating universes, but one of these is the largest structure we can see and another is the smallest:

Voroni pattern. It shows up in nature all the time.

First time I heard of this, super neat, thanks for sharing. Found a good article here:

God doesn’t play dice but he sure does repeat the same tune. I believe this same pattern is observable in our brains when neurons fire is it not?

There’s probably some math which explains the consistency of the pattern.

what’s the small one?

The little ‘3’ at the bottom right. That’s where the turtles live

I think the top is the small one because you zoom in really far on small things in rectangles. And the bottom is the universe because it’s a distorted view of a sphere, like our full view around us.

Atoms.

Or that the observable universe could be inside of a black hole. Don’t watch too many black hole videos before bed.

Planet 9 is not a primordial black hole and it can’t hurt you. 🙀

From my understanding of primordial black holes, if one were so close as to be in our solar system, it is very small.

Since it’s so small, it would have fizzled out through hawking radiation output a long time ago.

So yes, planet 9 is NOT a black hole that can hurt you.

Now, a pocket of warped spacetime that will one day spawn a Chaos Demon? Maybe.

It still fucks with me that we went from 9 planets to 8, pour one out for Pluto

Well at one time people “knew” that space was filled with Aether, and people knew that the universe was no more than 2 million years old.

But once you understand things more, some of the things you know turn out to be wrong.

In this case it’s more like “we called this thing a planet before we knew just how tiny it really is but it’s still cool so we now have categories for things just like it”

Which I think is neat.

You can be sad it’s not a planet, we can also be happy that it pulled one over on all of humanity for such a long time.

There are SO MANY Men In Black references in this thread and NOBODY is pointing them out and it is driving me CRAZY

That’s actually what I was going for but I didn’t want to use the “earth was flat” that K uses.

Ok thank you, that makes me feel a lot better to know that at least you intended the reference.

the only thing that changed is what we call it, pluto has existed since before humans and will continue to exist after humans most likely, and it does not give even the tiniest shit about what we call it.

“planet” is an arbitrary category that mostly just exists because we like to put things into categories, much like the concept of a continent.

It’s just really difficult to say that pluto is a planet if we want to have any sort of vague definition for what a planet is, because pluto is more similar to a ton of objects in the solar system than it is to the other bodies we very confidently refer to as planets.

If nothing else you have to also call ceres a planet if you include pluto, and how many people give a shit about ceres?

That’s messed up

I thought I heard once that our universe could be a holographic projection on a 2D plane surrounding around a black hole.

Don’t ask me for any details further than that, because I do not remember.

There was an episode of PBS Space Time on the holographic principle in general recently, and I believe they’ve also discussed the black hole thing as well.

Projected by what?

I don’t remember.

IIRC, isn’t it closer to a white hole, what with expansion? If you were far enough away, you cannot reach ‘there’ vs being guaranteed to reach ‘there’ like a black hole. Though really, it’s neither. Just curved spacetime.

The fact we think of white holes and black holes as separate entities just goes to show our great lack of understanding of spacetime.

My understanding is its similar in difference to a protostar and a nova

I mean, Schwarzschild radius shows that for a medium of constant density (and on a large scale, Universe is fairly uniform) there is an upper limit of a radius of a ball comprised of said medium above which it will form an event horizon.

Which means that an infinite universe of non-zero density is either a bloody paradox (spend a minute deciding where exactly event horizons should form and whether there will be gaps), or our understanding of gravity and spacetime breaks on ginormous scales just as it does on micro ones.

PS: I have seen no physicists talk about this, so there’s a good chance that there’s a simple resolution to the problem and I’m just stupid.

The galaxy is in Orion’s belt.

this is the ending to Men in Black (and then they did it again for the ending to Men in Black II because that film was creatively bankrupt).

“well brain, it seems you really need this sleep because that makes no sense whatsoever”

Considering how much shit orbits the sun that would be one wildly unstable atom

Nah. Sun just acts as the Queen Atom. Without it, you’d end up with a Helvetica Scenario. This is basic science.

everything written in a terrible font?

Oh. wrong Helvetica.

#commicsansforlife😁Please, jokes about this subject are very difficult for people affected by these situations. That is, it’s not the time to bring up comic sans, ok?

Me too

I had this thought as a kid. But I thought it was neat that we might be part of an atom of some larger molecule. Didn’t keep me awake. I had other trauma keeping me awake, like going to school.

I think this is why most people don’t think long on what "reality’ is. And can’t blame them, day to day life is difficult

Now imagine if something… or someone… would poke our galaxy with an observation, and all the stars in the arms instantly collapsed into a single particle.

There are better manners to avoid the sleep

I thought of this on the toilet when I was 14

Thanks, Neil degrasse Tyson

Doesn’t take a scientist to think about. We learn in middle school, atoms are mostly empty space, we learn small electrons revolve around a larger nucleus. All it takes a little imagination to put two and two together.

Yeah, we all learned it, you’re not special. I was calling you pretentious, not smart lol

So why is it keeping anyone up at night?

Edit: me not being special was my point, are you alright?

I’m alright, just misunderstood your original comment and tried to make a joke, my bad.

This is something I find believable, and I wonder why it’s not commonly discussed more.

you have to fail intro to qm 101 and/or be stoned out of your mind to think this way

Or just reject planck length and all other dimensional limitations like it. Then you can have

turtlesuniverses all the way down.Planck length is not like universal pixels. It’s just where current models say there’s little reason to look at smaller things, since it’s kind of like worrying about which flecks of paint are coming off a car in a racing video game. It’s just … so irrelevant as to be ignorable.

It’s nigh impossible to have any energy that could interact with us or atoms on the Planck length scale that wouldn’t just collapse in to a black hole. It’s not so much any observation of real-world pixelation, and more that even to atoms, it’s very tiny.

Your comment about current models, known energy types, and universal pixels seems to ignore the post’s topic (which isn’t really about known models or energy types).

A better way to disregard the post would be to just point out that solar systems aren’t that big in terms of scales of the universe, and that there’s no indication of any charges, electrons, or valance layers about.

I’m not responding to the comic. I’m responding to you talking about the Planck length. I’m not disregarding the comic but making a tangential comment. Please try to keep up.

No.

Your loss! 🤷

planck length doesn’t come up even once, it all boils down to these things: 1. electron has momentum, and from that follows it has a wavelength, and at the same time 2. orbit is stable, which means that after every “rotation” electron has to end up with the same phase, which means there is only a finite number of solutions to time-independent schroedinger equation for (hydrogen) atom (don’t bother solving it on paper for anything with more than one electron) and these things are spherical harmonics

And why is that?

planetary orbits are not quantized, for starters. atomic orbitals are occupied by pairs (at most) of electrons, and this is because of qm spin exists which has no analogue in large scale. electrons aren’t spinning around on an orbit, they’re more of a smudged standing wave. it’s also a staple among vapid thonkers like mckenna

Here’s a few reasons this doesn’t work:

- Planets are different sizes, electrons are all identical

- 2 planets cannot occupy the same orbit, but (at least) two electrons with opposite spin can

- If you have a high speed planet entering the solar system, you can’t transfer some of its energy to another planet and have the rogue planet continue with less energy

- All orbital energies are possible, not so much for atoms

- Planetary orbits emit gravitational waves. If electrons produced the equivalent (bremstrahlung radiation) during “orbit”, they would collide with the nucleus hilariously fast. This isn’t a problem because electron orbitals don’t have a physical representation.

Thank

Can confirm the latter makes you consider this

Can confirm, this is ALL I see on certain substances

it’s not commonly discussed because it’s wrong

You just need to know what happens to the elements on the periodic table that have the highest atomic weights. Here’s the article for Lawrencium give that a quick read through and then try to figure out why the universe is almost certainly not a very large atom as we define it.

It is in the right groups. Sort of thing you can find talked about at flat earther meetings all over the globe, UFO enthusiasts if you can get a word in to ask and in Christian science journals.

because it only seems believable if you’re using an outdated and simplified model for atoms, and forget about the fact that atoms are also made up of protons/neutrons who are in turn made up of quarks, and the fact that there are a whole bunch of other fundamental particles that don’t give a toss about atoms.

If you look at the more accurate electron cloud model it stops making sense to compare it to a solar system.