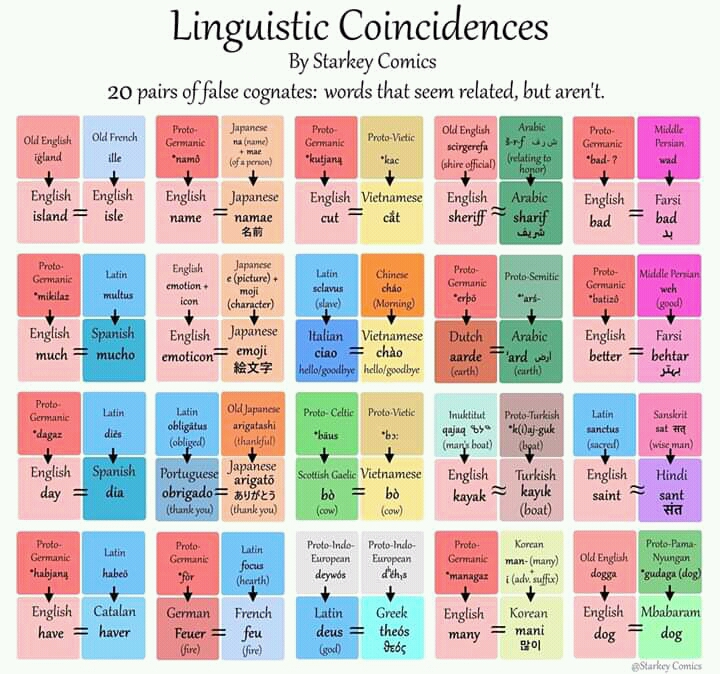

There is a table of examples in the link. Some I saw include:

Desert

- desert Latin dēserō (“to abandon”) << ultimately PIE **seh₁- (“to sow”)

- Ancient Egyptian: Deshret (refers to the land not flooded by the Nile) from dšr (red)

Shark

- shark Middle English shark from uncertain origin

- Chinese 鲨 (shā) Named as its crude skin similar to sand (沙 (shā))

Kayak

- Inuktitut ᖃᔭᖅ (kayak) Proto-Eskimo *qyaq

- Turkish kayık (‘small boat’)[17] Old Turkic kayguk << Proto-Turkic kay- (“to slide, to turn”)

A lot of these could be TIL posts of their own.

I also wonder if some of these are actually false cognates, or if there is a much earlier common origin with false associations that came afterwards

Ass as in donkey and ass as in butt have different etymologies. The donkey one likely comes from Latin asinus and the butt one is from dropping the r in arse, which comes from the PIE root *ors- meaning butt/backside

deleted by creator

Ah my favorite false cognate isn’t here, that means I get to post about it!

Emoticon :) is emotion + icon in English, invented in the 80s or early 90s. Exactly what you think.

Emoji is Japanese 絵文字 which basically translates to “picture character”. That word has been around for a long time; I don’t know that I can put a date to it. But certainly a lot older than computers.

They just happen to sound similar

Oh wow, I assumed they were related :)

Related fun fact: emoji is the plural, and the singular is emojus!

Well, no, it’s not, since emoji is not a Latin word. It is a fun factoid though!

Right, for sure if you were to pluralize emoji (which is singular) it wouldn’t be emojus in japanese.

I was gonna toss some guesses here but it’s a word I don’t think you pluralize really, as we don’t in English

Japanese doesn’t have different forms for plural, so “emoji” can be both singular and plural.

yeah, if anything they might collectivize it like “emoji-tachi”. though I’ve never heard it used that way.

I also wonder if some of these are actually false cognates, or if there is a much earlier common origin with false associations that came afterwards

Common but old origin tends to make words diverge over time. Compare for example:

Old languages Modern languages Proto-Germanic */fimf/ English ⟨five⟩ /'fa͡ɪv/ Latin ⟨quinque⟩ /'kʷin.kʷe/ Italian ⟨cinque⟩ /'t͡ʃin.kʷe/ Proto-Celtic */'kʷen.kʷe/ Irish ⟨cúig⟩ /'ku:ɟ/ Sanskrit ⟨पञ्चन्⟩ /'pɐɲ.t͡ɕɐn/ Hindi ⟨पाँच⟩ /'pɑ̃:t͡ʃ/ All those eight are true cognates, they’re all from Proto-Indo-European *pénkʷe. But if you look only at the modern stuff, those four look nothing like each other - and yet their [near-]ancestors (the other four) resemble each other a bit better, Latin and Proto-Celtic for example used almost the same word.

They also get even more similar if you know a few common sound changes, like:

- Proto-Italic (Latin’s ancestor) changed PIE *p into /kʷ/ if there was another /kʷ/ nearby

- Proto-Germanic changed PIE *p into *f (Grimm’s Law)

In the meantime, false cognates - like the ones mentioned by the OP - are often similar now, but once you dig into their past they look less and less like each other, the opposite of the above.

They also often rely on affixes that we know to be unrelated. For example, let’s dig a bit into the first pair, desert/deshret:

- Latin ⟨deserō⟩ “I desert, I abandon [unseeded], I part away” - that de- is always found in verbs with movement from something, or undoing something. It’s roughly like English “away” in

trennbarephrasal verbs like ⟨part away⟩, ⟨explain away⟩, ⟨go away⟩ - Egyptian ⟨dšrt⟩* “the red” - the ending -t is a feminine ending, like Spanish -a. And the word isn’t even ⟨deshret⟩ in Egyptian, it’s more like /ˈtʼaʃɾat/

Suddenly our comparison isn’t even between ⟨desert⟩ and ⟨deshret⟩, but rather between /seɾo:/ and /ˈtʼaʃɾa/. They… don’t look similar at all.

* see here for the word in hieroglyphs.

Other bits of info:

- ⟨shark⟩ - potentially a borrowing from German ⟨Schurke⟩ scoundrel. Think on loan sharks, for example, those people who chase you over and over; apply the same meaning to a fish and you got a predator, a shark fish. Note that the old name of the fish (dogfish) also hints the same behaviour.

- Turkish ⟨kayık⟩ - the word is attested as ⟨qayğıq⟩ in Khaqani Turkic. I might be wrong but I think that the -yık (Old Turkic “guk”) forms adjectives, as the Azeri cognates that I’ve found using this suffix are mostly adjectives; see qıyıq, ayıq, sayıq. Kind of tempting to interpret it etymologically as something like “sliding boat”, with the “boat” part being eventually omitted.

Very cool, thank you for the detailed breakdown that was helpful!

How did ‘slave’ become ‘ciao’?

The image is simplifying it, but Italian borrowed the word from another Romance language, called Venetian. Latin sclauus /'skla.wus/ “slave, serf, servant” → Venetian scia(v)o /'stʃa(v)o/ “slave”→“bye”. Then Italian borrowed it from Venetian, and it ended as ciao /tʃao/ because Italian hates that /stʃ/ cluster.

The meaning evolved this way because of mediaeval humility expressions, like “mi so’ sciavo vostro”. It means literally “I’m your servant”, and it implies that I’m eager to fulfil some request that you might have.

A similar expression pops up in Southern German; see servus.

Ah okay, Christian medieval traditions are weird.

Very cool! This could go in !coolguides@lemmy.ca as a post of its own