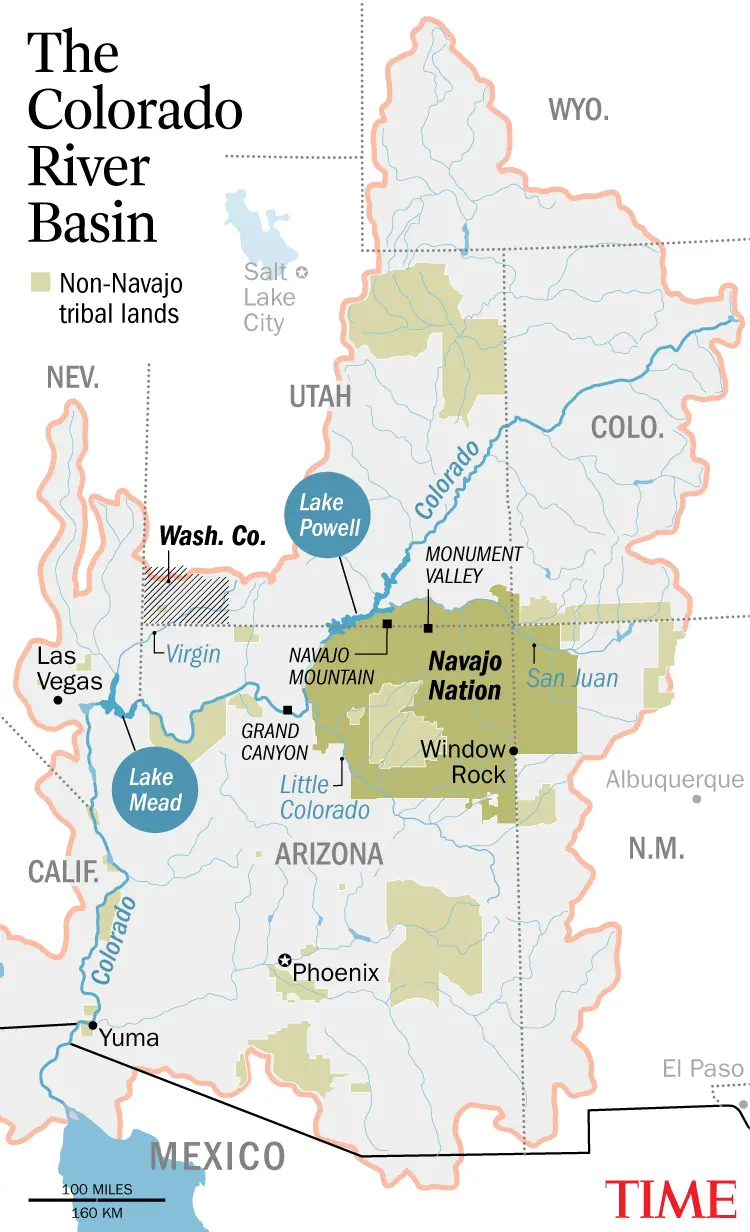

In the Navajo Nation—a sweeping landscape of red-rock canyons and desert that takes in the Four Corners—water is not taken for granted. Here, more than 1 in 3 Diné, as Navajo people call themselves, must haul water to their homes, often across long distances. The Diné use the least amount of water per person of anyone in the U.S., and pay the most.

The problem, as old as the land itself, was predicted. The hydrology of the Colorado River Basin is highly variable, a fact that was not fully appreciated (or was flatly ignored) by those who drafted the foundational policy that governs water use in much of the West—the 1922 Colorado River Compact. Despite warnings from experts, the compact based the amount of water to be divided among its signatories on a brief period that proved to be one of the wettest in history. This flaw was compounded by tremendous population growth, Indigenous dispossession, competing values, procrastination, and deadlocked disputes over how water is used.

On paper, the Navajo Nation is drenched in water. Under the “first in line, first in right” principle that defines water use in the West, the Diné have first dibs on the same declining supply that serves Washington County, which has roughly as many people on one-tenth the land: the Colorado River, its tributaries, and two underlying aquifers. Yet little of it reaches them. In 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in Arizona v. Navajo Nation, that the federal government has no obligation to provide water to the Navajo Nation. But by the time of the ruling, a crucial exercise of “first rights” was already in peril.

The Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project aims to deliver treated water from the San Juan River to 240,000 people via 300 miles of pipes. Conceived in the 1960s and begun in 2009, the $2.1 billion project must be completed by Dec. 31 or the Navajo Nation loses its right to that water. It’s far from done. Its fate resides in U.S. House Bill 3977, which would extend the deadline to 2029 and appropriate $689.45 million to finish the job.

Washington County isn’t the cause of the Navajo -Nation’s thirst. The water gap is an enduring legacy of manifest destiny; the infrastructure, and legislation, that came with it still largely define how water is used. In the American West, irrigated agriculture uses a whopping 86% of fresh water consumed—the largest share by far going to animal-forage crops like alfalfa. Privately, a St. George resident told me, “Why should I compromise the things that bring me enjoyment when alfalfa is still being grown? I hate to say that out loud, but that’s the reality.” On the other hand, since 2002, water–strapped Southern Nevada, including Las Vegas, cut its use by 26% while adding 750,000 people—proof that measures like the Post-2026 Operational Guidelines really matter.